This article was written by Grant Headifen of NauticEd Sailing School.

As you learn to sail and advance your knowledge, it’s important to learn the finer point of sail trim and understand what is going on with the wind in the sails.

We approach this topic by looking at the condition created by an incorrect trim setting of the mainsail causing rounding up. Rounding up is when your sailboat, against your will, automatically turns up into the wind. If you understand how your sailboat should not round up then you will understand the proper trim of the mainsail.

Rounding up is caused by many factors. One is too much wind and force aloft which tends to heel the boat over. This reduces the amount of rudder in the water and thus the rudder’s effectiveness. According to Pythagoras’ theorem a 30 degree heel will loose you 29% of your rudder effectiveness. This means you’ll need more helm to weather to control the boat. More helm to weather creates more drag. More drag slows the boat. As the boat slows the rudder becomes far less effective by the square of the reduced velocity. So with over heeling you’re loosing rudder area and velocity. A cubic reduction in effectiveness to control a round up.

Another factor in rounding up is the center of pressure of wind on the sails moves far aft which then pushes the aft of the boat downwind and thus the front of the boat up wind.

The NauticEd SailTrim clinic discusses this topic and so what we wanted to do was test it out for sure. So last weekend we took out a friend’s Beneteau 373 to test out an anti-round up theory. Read on to find out the results of our experiment.

First though, we must first understand wind shear. The phenomenon of wind shear is pretty easy. Wind moves faster at the top of the mast than is does at the water level because the stationary water slows the down the wind in close proximity.

Secondly, consider the concept of true wind vs apparent wind. Which is best understood by imagining driving your car in a cross wind with your hand out the window of the car. The faster you go, the more the apparent wind moves towards coming from the front of the car. But when a gust of wind comes (which is just an increase in true wind speed) then the apparent wind shifts back more to the side. When relating this to a sailboat, if your boat was standing still, the wind at the top of the mast would be the same apparent direction as at the cockpit level albeit, faster. However as your boat picks up in speed the apparent wind moves forward BUT because of wind shear it shifts forward less at the top of the mast. IE at the top of the mast the wind tends more to the direction of true wind direction because the true wind speed is higher. Thus at the top of the mast the true wind is more aft than apparent wind. Aft means it is coming from a direction further towards the back of the boat. Get it?

So – whether you get it or not. The fact is: at the top of the mast the wind is higher in speed and more aft than at the cockpit level.

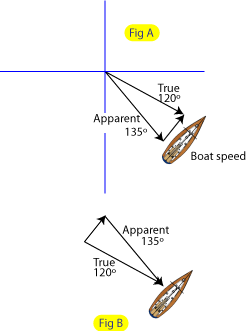

true wind vs apparent wind

Figure A and B show the boat speed, true wind and apparent wind vectors for cockpit level and top of the mast. Obviously in both cases, the boat speed vector must be the same. The true wind vector is obviously the same direction but due to wind shear it is longer (faster) at the top of the mast. This results then in the apparent wind direction being more aft. IE in this case from 135 deg to 125 deg.

Thirdly, you should understand that if a sail is sheeted in to tight it creates more heel. This then is exactly what is happening at the top of the mast. The sail is sheeted in too tight against higher wind speed. No wonder you’re getting excessive heeling. And excessive heeling creates round ups.

This is now quite a revelation! It means that the top of the main needs to be “out” further than the bottom of the sail for it to operate efficiently. This is usually indicated by the top telltale. Often the leeward telltale will be stalling at the top of the sail. Especially in high wind because of the phenomena above.

Thus the top of the mainsail needs to be let out further so that the leeward telltale can fly smoothly. This is commonly referred to as twisting the sail out at the top. Except people believe you are just spilling out (wasting) the wind at the top. Not quite so now, as you’ve just learned. Twisting out the top of the sail is letting the top of the sail fly according to the direction of wind it is feeling.

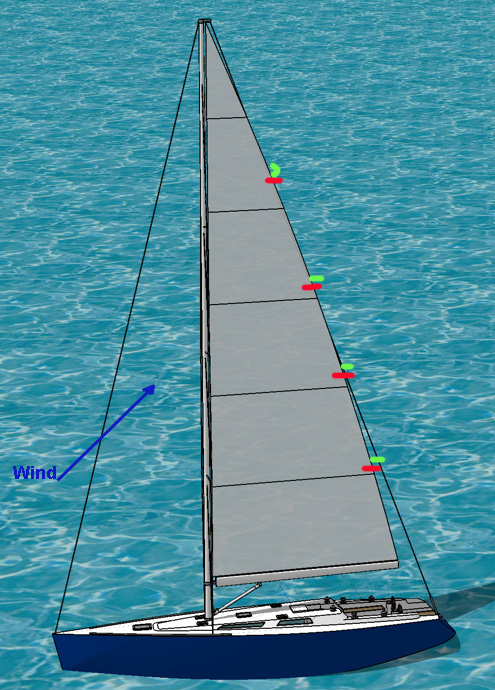

Tell tales on the sail

In the illustration, you can see the top telltale on the downwind side is fluttering. If you let out the main at the top, the wind can reattach to the sail on the leeward side and the telltale will fly smoothly.

Understanding all the above. How do we stop rounding up?

Option one: Obviously the first and safe option in higher winds is to reef the sail but the options below will still apply.

Option two: Let out the traveler, which is what most people do when hit by a gust. Just so long as you realize what you’ve done is not twisted the top of the sail out – all you’ve done is let out the mainsail from top to bottom and thus depower the mainsail. This reduces the force aloft and thus the heel. It also moves the center of effort of wind on the sails forward which reduces tendency to round up. The trouble is that you spend all day fighting gusts with still quite a few involuntary round-ups.

Option three: Let out on the mainsheet. Here again you’ve depowered the entire mainsail to handle the gust. Still, it works.

Option four: Permanently reduce the force aloft by letting out further on the mainsail and tightening up on the traveler. The trick here is to bring the mainsail bottom back in again using the traveler. Yes, bring the traveler to windward up past the center point. Most sailors are reluctant to do this because they’ve been taught that it detaches the wind on the leeward side. But not when you’ve let out the mainsheet. In effect, by letting out on the mainsheet, you’ve allowed the boom to rise up and the leech of the sail to slacken. This creates the desired twist at the top and allows the top of the sail to fly according to its apparent direction. At the same time, the bottom of the sail can fly according to its apparent direction.

What happened on our 15 knot gusty sailing day? Well, not one round up.

So to summarize, the sailing lesson here is when in higher winds bring the traveler up and sheet out the main. You’ll also need to release the boom vang a little. Letting the boom vang out allows the boom to rise which loosens the leech (trailing edge) of the sail and allows the top part to “twist out”.