This learn to sail article was written by Grant Headifen, Educational Director of NauticEd. NauticEd is an online sailing school and Sailing Certification Company providing sailing courses and sailing certifications for beginner to advanced sailors.

During the Americas’ Cup campaign in New Zealand in 2003, I saw one of the best explanations of this on a TV interview with the Greg Butterworth, the Tactician for the Alingi Team.

Most of us sort of understand the concept and we’ve been left with the answer of “Well – weather helm is better because it’s safer.” But few explanations go into how it gives your boat a sailing advantage. This concept is also explained in our Sail Trim Sailing Course on-line.

The definition of weather helm and lee helm is simple and it is easy to remember which is which. If you have a tiller, weather helm is when you have to pull the tiller to weather (toward the wind) in order to keep the boat going in a straight line. Lee helm is when you push the tiller to lee (downwind) in order to keep the boat going in a straight line. We’ve probably all felt this slight pressure required on the tiller when underway. If you’re just learning to sail, remember next time you’re out to feel for this on the wheel.

Your boat can be tuned to give weather helm or lee helm. Rake the mast forward and you move the center of effort of the wind forward which causes your boat to want to turn downwind. Rake the mast back and you move the center of effort of the wind back causing your boat to want to go upwind to weather.

When your boat gets rounded up – you just experienced massive weather helm. No matter how much you pull the tiller to weather, you can’t stop the boat going to weather. Dumping the main sail moves the center of effort forward thus reducing the weather helm.

The basic perception of weather helm being safer comes from this effect: if you let go of the tiller, it will automatically go to center because of the water flowing over the rudder and because the rudder is pivoted at its leading edge. Now there is no rudder force to counter the desire of the boat to turn up wind to weather so the boat does exactly that. It turns to weather and rounds up thus slowing the boat down and reducing forces on the rig. Conversely, lee helm means that if you let the tiller go the boat will turn away from the wind, heel over more increase forces on the rig.

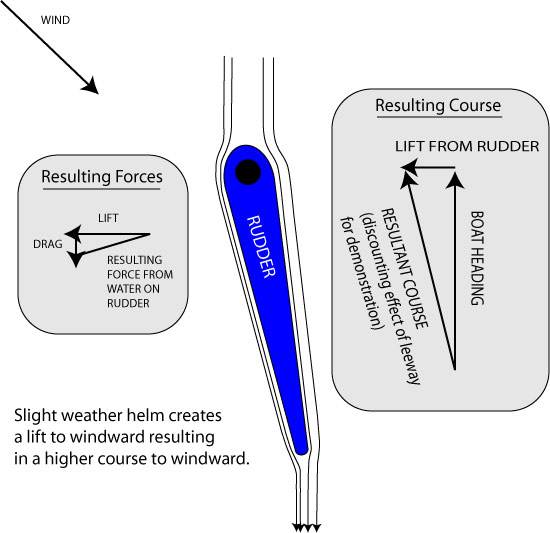

So from a safety point, weather helm is good. BUT there is another advantage that we’re not generally taught. Holding the tiller to weather means that there is a slight pressure on the rudder to windward. This actually MOVES THE BOAT TO WINDWARD as it slices through the water. And we all know what that means, race advantage!

The illustration shows how the water pressure from weather helm creates a sideways force on the rudder tending to push the boat to weather.

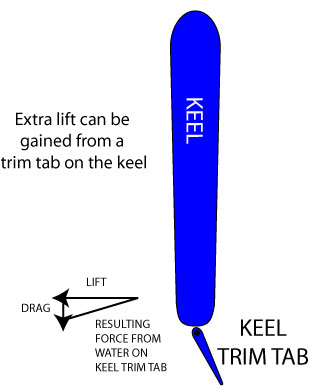

Now Greg Butterworth went on to explain that there are other cool things you can do. One is to put a little trailing edge swinging control surface on the keel.

The illustration below shows this effect too. For us pilots, this is much like a trim tab on a wing of a small airplane. The trim tab creates the ability to adjust the lift at that point on the aircraft and thus create a balance of forces. The issue to remember here is that you’d need to trim the tab the other way when you tack over.

So there you have it. While we’ve all been understanding the lifting effects of the wind over the sail, the other fluid that we’ve ignored is the water under the boat and how we can gain lift from it too.

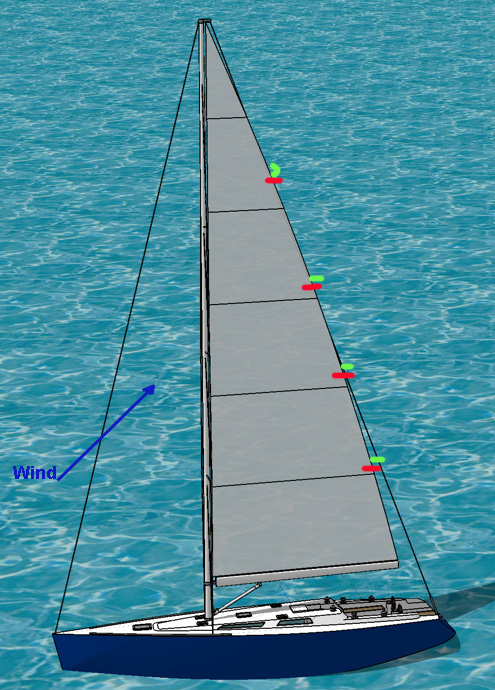

Next time you’re out sailing on a nice steady 10 knot breeze, come up on a close haul, trim the sails perfectly so that all your tell tails are flying smoothly. Then notice what pressure you’ve got on the helm. Note that if you’ve got a wheel, weather helm will be a tendency to apply downwind turning pressure on the wheel (which is the same as pulling a tiller upwind right?). Ideally you should have slight weather helm. If not, you should probably not jump right in and start raking your mast back. Talk to a mast tuning specialist in your area first.